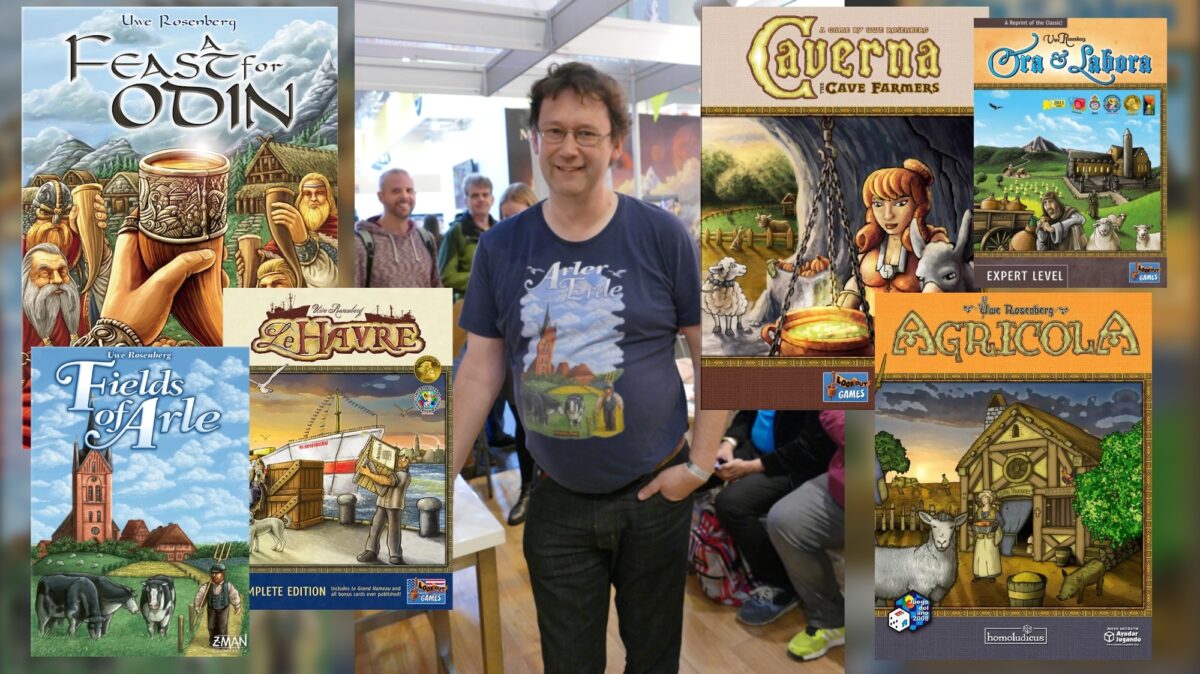

Uwe Rosenberg is a German board game designer with several highly respected titles in his ludography. If there’s a designer whose work I adore, Rosenberg is that.

He has designed many games, but I’m particularly interested in his work around the farming theme and worker placement mechanism, starting from Agricola in 2007.

This ignores his early work with clever card games, like Bohnanza in 1997, and his later polyomino game work, like Patchwork. That’s fine.

Agricola (2007)

The start of the farming revolution. I remember playing this fresh when it was released. Actually, one of the joys of having a blog with twenty years of back archives is not having to remember things: here’s the blog post from 2007 describing my initial impressions of Agricola.

So, yes, I love it. After that first game the game jumped from “hmm, this seems interesting” to “must buy as soon as the English edition arrives”. I’m waiting — there’s just too much German. It’s not that bad, at least except for the cards, but still I’d rather wait.

Of course, I didn’t wait for the English edition; I had to get the German edition and then translate the cards in Finnish myself (later, I ended up doing the official Finnish translation for the Agricola Revised Edition).

Agricola was a smash hit and did wonders for making worker placement a common game mechanism. People still play the game, and it has received new editions, lots of expansions and has reached at least a cult classic status.

I’ve moved on, and I don’t even have a copy anymore. It was an easy decision after realising I always preferred the new games. Also, this has never been a hit in my game groups, and I’ve never really wanted to play this with large player counts, including newbies because the game is just too slow that way.

Le Havre (2008)

Next year Rosenberg followed up with Le Havre. Agricola was named after the Finnish archbishop who translated The Bible in Finnish, and this follow-up was named after the Kaurismäki movie of the same name. How very Finnish!

In Helcon 2008, I tried Le Havre (the relevant blog post). I liked the game a lot but also thought it was too long. That’s still the only time I’ve played Le Havre (I may have played the app version once or twice). That’s something of a shame; I have a feeling I’d enjoy it.

I do know that before Nooa, I wouldn’t have had enough opportunities to play the game, and later when the circumstances were better, there were already other games. But I’ve been thinking about giving Le Havre a new go. If only the local library had a copy!

At the Gates of Loyang (2009)

After Le Havre, I stopped following the releases of the new Rosenberg games. In 2009, my board gaming time was at an all-time low, and I figured out most Rosenberg games were just too long as multiplayer games (I play all of these as two-player games these days). This game entered my life in 2015.

At the Gates of Loyang is a Chinese-themed game of farming and selling the product to customers who require commitment: you must deliver the products many times, and if you fail, the customer gets angry. It’s a lovely challenge and gives you plenty of space for being clever.

One of the delights in this game is the scoring. You need to buy your progress on the scoring track. The first step of each turn costs you one point. After that, the price you pay is the number of the space you’re moving to. Buying extra steps earlier in the game is very important, but you also need the money to develop your engine. Even though I like the puzzle, this didn’t get enough play, so I passed this one along to a new home after just four plays in three years.

Fun fact: the main website where I test my WordPress plugin code is called Loyang.

Merkator (2010)

Something of an outlier, Merkator isn’t terribly popular. It’s not about farming or worker placement, but instead a game of collecting goods, delivering them to fulfil contracts and getting better contracts. There are several clever things in this game; one of my favourites is that delivering to a contract doesn’t make the contract go away; you can deliver to it again until you decide to sell the contract.

I first got Merkator in 2015, but it took me a few years to figure out the game with Nooa. Now we have realised it’s a marvellous filler game. We can play this really fast: the box says 45–90 minutes, but our games take 20 minutes, tops, and we’ve played games that have taken just ten minutes.

Played that way, Merkator is a thrilling race to more valuable contracts before the time runs out. I wouldn’t dare to recommend it to anyone, really, but for Nooa and me, it’s very, very good.

Ora et Labora (2011)

I was aware of Ora et Labora when released in 2011 but promptly dismissed it as too long. It probably was, but when I had home-grown a co-player, I bought a new second printing copy of Ora et Labora in 2016. It turned out to be a success.

This monastery-themed game is also one of the reasons I haven’t looked into Le Havre much. I’ve understood Ora et Labora is something of a Le Havre 2.0. I’m not sure how true that is in the end, but this is how I have perceived the matter.

In any case, this is a delightful game of managing workers and resources. This isn’t a game of limited resources; the game throws stuff at you, but it’s a puzzle to make sure you have the correct goods at the right time. Ora et Labora has the update mechanism of Le Havre: you can get sheep, but it’s better if you then spend time and effort flipping the sheep tiles to get the processed meat side upwards.

Ora et Labora is quite fiddly, and while I wouldn’t say no to a four-player game, it’s somewhat clumsy when you have to see what small cards your opponents have on their tableaus. It is not convenient. In the two-player game, this isn’t a significant problem.

Agricola: All Creatures Big and Small (2012)

Uwe Rosenberg did a series of small-box two-player game versions of his bigger games, starting with Agricola: All Creatures Big and Small. This isn’t a bad game; it doesn’t really try to be too much like the big Agricola. The challenge is built of standard components but is different.

I find this game remarkably ok. I wouldn’t say no, but my copy did find a new home after a dozen plays. The elements of this game later resurfaced in Lowlands; this isn’t a Rosenberg title but is clearly in debt to Agricola: ACBAS, the buildings work in such a similar fashion in that game.

In the end, I think one of the problems is that Uwe Rosenberg games are generally already excellent two-player games and play reasonably fast, so there’s little need for two-player variants that are slightly faster.

Le Havre: Inland Port (2012)

However, this two-player version of Le Havre was quite unlike anything else. Inland Port was a good game we enjoyed when Nooa was nine-ten years old; now he’s older, we rather play the big Rosenberg games. We enjoyed this one too for about a dozen plays.

Again, this wasn’t as small and handy as it could be, compared to the bigger games. There’s a specific title on this list that made these small-box games obsolete; we’ll get to that later.

I think these two-player games are well worth experimenting with for those who find these two-player games more compact and much faster than the originals. Inland Port, in particular, has exciting resource management and building action, reminding you of the original Le Havre but still quite unlike it.

Glass Road (2013)

Glass Road is a curious game. Usually, Uwe Rosenberg games are very good with two players (or even solo) and don’t get any better with extra players, just longer. Glass Road, however, I’m not as sure. BoardGameGeek audience does think Glass Road is best with two.

Glass Road is a concise game: just four rounds. Especially when you’re new, it seems curious how you can achieve anything in this game, but once you figure out how the game works and how the buildings are best used, it gets easier to fill the board with buildings.

The game also has a clever resource tracking mechanism that borrows the resource wheels of Ora et Labora. In Ora et Labora, there’s one resource wheel, where tokens are used to track the number of resources available, and a simple turn of the pointer adds one resource to each type. This is a brilliant bit of optimisation, compared to adding resource tokens on cards as in Agricola or Le Havre.

In Glass Road, each player has two personal resource wheels. One is linked to bricks, the other to glass. Once you have enough resources on the wheel, it automatically turns, eats your primary resources and produces brick or glass. This is clever, as you generally want these valuable resources, but not always.

In the end, the second-guessing mechanism involved in this game wasn’t my cup of tea, and in my opinion, this is something I’d rather play with more than two players. That wasn’t really an option, so Glass Road left my collection.

Caverna: The Cave Farmers (2013)

Many people consider Caverna: The Cave Farmers to be the better Agricola. It replaces the real-life farming theme with fantasy dwarves dwelling in caves, but it’s still the same Agricola underneath. You still farm the fields and keep animals in the forests outside your cave, but now you also dig mines in the cave and build rooms that grant you special powers. You can also go exploring for better and better rewards by improving the military capabilities of your dwarves. This upgrading makes some workers worth more, which is interesting.

I’ve played it a couple of times with a library copy, but it didn’t click for me. For me, the theme in Agricola is more attractive, but the biggest problem with Caverna is still the way it presents you all the possible room upgrades at once. Pick a room, pick any room!

Ugh, no. That’s just too much, too many options. Too much freedom? In any case, to me, this was an exciting game to try. Still, Agricola was more attractive, so once I had to return Caverna to the library, I have had very little interest to get back to it, as newer titles have surpassed it in my mind.

Fields of Arle (2014)

Since many Uwe Rosenberg games have been best with two players, Fields of Arle only supports two players. That’s a bold move with such a big box game in a genre where multiplayer games are the norm. But it works really well, even if the Tea & Trade expansion adds a third player (an option I’ve yet to try).

This is also Uwe Rosenberg’s most personal title. Rosenberg was born in Aurich in East Frisia, where Fields of Arle is set. Many unique details are connected to Rosenberg’s family history in this game.

I find Fields of Arle a marvellous work and the main reason I don’t play Agricola anymore. This is such a rich experience, with lots of things to do. Farming, animal husbandry, building… many different paths open before you, and all are interesting.

Even though the game has no random elements outside the random draw for a couple of buildings at the beginning, I still find myself playing different strategies. It would be easy to get stuck in a single approach here, but Fields of Arle offers such a smörgåsbord of options that I find myself drawn to many directions. The Tea & Trade expansion does great work expanding these options without unnecessarily complicating things.

A Feast for Odin (2016)

After cranking out a game per year, if not more, all the way from Agricola in 2007, Uwe Rosenberg had a weak year in 2015. His only game release was Hengist, which was universally panned.

Never mind, because, in 2016, we got A Feast for Odin, a massive box of Viking goodness. Combining worker placement with polyomino tile placement of Patchwork, A Feast for Odin is a great game of resource management. Players place their Viking workers to take actions hunting, fishing, whaling, trading, raising animals, exploring and of course, Vikings as they are, raiding and pillaging.

The results of all these actions are tiles of various shapes and sizes. Basic farm goods are orange and better foods are red. These can be stored in storage houses to gain benefits and points, but your main player board and the explored island boards only take goods, which are green and blue tiles. The tiles can be upgraded from orange to red to green to blue. The boards have bonus spaces, which can be encircled to gain income. Building a good engine will make life easier.

There are many options in this game, many things to do. The best actions are costly: the cheapest actions only take one Viking, but the best require four. That’s a hefty price to pay, but the benefits are worth the effort.

There’s an excellent expansion for A Feast for Odin. The Norwegians expansion upgrades the action selection boards, improving the two-player game and providing more variation. The Harvest is a mini-expansion but dramatically improves the game by making the shorter version more exciting, thanks to bootstrap rules that speed up the beginning of the game.

Gernot Köpke, the developer of The Norwegians, has been busy working with new expansions to the game. He has great plans, none of which have materialised so far. Next up is The Danes, which should be coming out in 2022 as a standalone expansion. It’ll be interesting to see where that takes A Feast for Odin. As it is, the game is currently my favourite of the Uwe Rosenberg titles.

Nusfjord (2017)

After three big games in big boxes, Uwe Rosenberg took a step to smaller games in the shape of Nusfjord. It’s still worker placement, but in general is more in the way of Glass Road what comes to size and scale (mechanically, the games don’t have much in common).

Each player gets a personal board and three workers. During seven rounds, players acquire fish from their fishing fleet, fell trees to get wood and issue shares to gain gold. These resources are then used to buy new ships and build buildings that provide various immediate or ongoing benefits.

Everything is powered by a straightforward worker placement engine, with three workers per player. Rounds are short, and our two-player games take about 20 minutes. This short and sweet length is the main reason why Nusfjord shine. It shines so hard it eradicated the small-box two-player games from my collection.

The buildings are what provides the variety here. The base game comes with three different decks of buildings, each with their personal flavour, and expansions have since offered two more. Hopefully, more will come because Nusfjord is a very attractive game of coming up with combos of buildings and more variety is always good in a game like this.

Caverna: Cave vs Cave (2017)

This is the small-box version of Caverna: The Cave Farmers. A delightful game it is, likely the best in the series. This, too, lasted about dozen plays in my collection, even though it even got an expansion.

In Caverna: Cave vs Cave, players dig out their caves and build rooms inside. The actions are selected from a row of choices that expands as the game goes on. This action selection mechanism works well, as you have to constantly think of what you need and what you want to deny from your opponent.

It’s also nice how all the rooms are not always available. A basic set of rooms is constant, but most of the rooms start the game face down as cave tiles. Once players dig out to expand their cavern, the tiles come into play as buildings. Eventually, most buildings will be available, but their order is random.

The Iron Age expansion adds a second phase in the game. More rooms are available, and the technology gets more advanced, with iron, weapons and donkeys. This provides more variety, but on the other hand, the second phase doubles the game’s length. Especially with the expansion, Caverna: Cave vs Cave is a much longer game than Nusfjord, which I feel packs more punch and more variety.

Reykholt (2018)

Reykholt is a redevelopment of At the Gates of Loyang: the games share the same farming mechanism and similarities in scoring. However, they are different games, and Reykholt isn’t even listed as a redevelopment of At the Gates of Loyang on BoardGameGeek. But the connections are there.

After hearing the initial buzz, I was cautious. I did get the game on loan from a friend, played it once and figured out it’s not for me. It’s just so bland. The worker placement options weren’t exciting, and the scoring didn’t feel good for me.

Reykholt is probably too streamlined. I’d rather play the more complex challenge of At the Gates of Loyang. I wonder if being published by a newcomer, Frosted Games, has something to do with this? Perhaps better development would’ve improved the game. Who knows; all I know is that this game didn’t push my buttons.

Hallertau (2020)

But this one did! Uwe Rosenberg has told Hallertau is his final big box farming game, at least for the foreseeable future, as he focuses on smaller games that better suit his busy family life. That’s a pity, but on the other hand – with this line-up, who can really demand more?

This selection should keep any board game enthusiast happy for a long time (and if these games don’t work for you, do really you expect Rosenberg to create something that does?)

Hallertau has been in the works for many years, it took a long time to go through all the development process steps, but it’s worth the wait. While many of the games on this list are very low on luck, Hallertau has a strong random element in the shape of cards. The cards are critical and push your game in many directions. You better follow where the cards want to take you!

I really, really like that. Many of my favourite games are like that: you get cards and do what you can with them. Hallertau is precisely that. Outside the cards, it’s another take on worker placement. Each action can be taken three times, every time with a higher cost. The action spaces are only partly emptied between the rounds, so the most popular actions are not available all the time. Better do something else, then!

The fundamental goal of the game is to advance your community centre by paying resources to move craft buildings forwards on the track. This gets more expensive during the game, so once again, it’s the Loyang balancing act between advancing your score and building your engine. Doing things a little every round is much cheaper than rushing a lot at the end.

All in all, Hallertau is an excellent game.

My top five

My personal Uwe Rosenberg farming game top five is clear. On top, there’s A Feast for Odin. It’s my favourite, it’s just so heavy and full of exciting things. A very close second is Fields of Arle. This, too, is an excellent game I always enjoy.

Next up are Nusfjord, because it’s such a short and sweet game, and Hallertau, for the clever use of cards. Finally, the fifth place goes to Ora et Labora, which takes the resource management to a delicious level, and the tableau-building element is also gorgeous.

I’d be happy to play all of these games, except Reykholt.

BoardGameGeek ranking

As I’m writing this in December 2021, the current ranking of these games on BoardGameGeek is:

- A Feast for Odin

- Caverna: The Cave Farmers

- Agricola

- Le Havre

- Fields of Arle

- Agricola (Revised Edition)

- Ora et Labora

- Glass Road

- Agricola: All Creatures Big and Small

- At the Gates of Loyang

- Nusfjord

- Hallertau

- Caverna: Cave vs Cave

- Merkator

- Le Havre: The Inland Port

- Reykholt

A Feast for Odin, Caverna and Agricola are in the top 50. Fields of Arle and Agricola (Revised Edition) are in the top 100. Ora et Labora, Glass Road, Agricola: ACBAS, At the Gates of Loyang, Nusfjord and Hallertau are in the top 500. Caverna: Cave vs Cave is in the top 1000.

2 responses to “Uwe Rosenberg farming games”

Perfect list for me. After a long break, I’m playing Agricola at BGA. I haven’t been keeping track of Uwe’s games so this is perfect timing. 😀

A Feast for Odin is also available at BGA (in beta, I think).